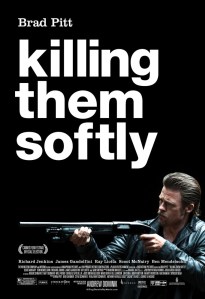

We like to imagine that we’ve cleared the orbit of the circle of life. That we’ve achieved a degree of self-awareness far greater than that of our savage forbears, and a good distance from the antiquated notion of hunters and prey. The reality is that we’ve created a new circle of life, one in which we are the sole patrons, and the money is the mission. This is the world according to Writer/Director Andrew Dominik‘s latest, Killing Them Softly, a film as well-made and intriguing as it is heavy-handed and bleak. Softly is a gritty crime allegory, allowing a hierarchy of gangsters to stand in for our nation’s government and its people, and as the film unfolds it expends loads of energy conveying this connection, asking blood and gore to serve as a proxy for dollars and cents.

Author

-

-

Recent Posts

The Breakdown